The Woman I Know: The Feminism I Learned from My Grandmother

Growing up in a military family, I would listen to my father talk about the sacred land we live on. He was passionate about the country that he served and tried to bestow the same sentiments in his children, but, at that time, I didn’t feel anything. It seemed more like a duty everyone did obliviously in their mundane routines without much effort. For me, living in Pakistan was equivalent to loving Pakistan; like everyone around me, all my true patriotic sentiments were layered with materialistic indifference. However, all the surfacing ideas of the mystic land that I called home took a turn when I left home to live with my grandmother (who I call Ammi) at the age of 15.

She is your normal old person. Wrinkled skin, hair dyed in a shade too black and hobbies that involve gardening, scolding everyone and living her fragile remaining life in the most ordinary fashion. On weekdays, Ammi drives to work in her small beaten-up gray car, and on the weekends, she often takes out her collection of hunting rifles and spends hours polishing them with the finest macadamia brown tint.

In the time that I spent with her, our relationship could only be described as a game of Jenga. She pulled out all the wrong blocks in me, breaking the tower of my superficial worldly notions of womanhood, and then reconstructed my persona with an innovation that I had thought impossible. “You are an incomplete woman. These grades or your English schooling will not make you a wholesome person. Neither will a man or your career.” I wondered if she was talking about religion, but she simply said, “you are following what the ‘angrez’ (English) gave us, and we are not angrez women. We have brown skins and no rights in a land owned by illiterate men. Go out there and try talking to a woman whose daughters have been murdered by their own father for speaking up for themselves, sit next to an acid victim and ask her how she eats, or just stand outside and look at the face of the garbage lady who eats your leftovers.”

She simply hated Western feminism. She hated the fact that I wanted equal rights for women at the workplace, because the majority of lower-middle-class women in my country were not even allowed to work, let alone paid for the little work they did. My Western feminist notions slowly began to die as I found myself standing behind Ammi, looking upon the things she did for women and for her own daughters.

Ammi would tell me infinite tales of the land that she had once called home, Shimla India. The place where she lived in a house too big with a crowd too homely. She tended elephants, went to college, learned gymnastics, cooked food, played in the green land, and ate lychees the size of her palm. But soon, the elephants began to disappear one at a time, the green that had once surrounded her turned into the most disgusting shade of brown, and the crowd that had once lived satisfied was now fleeing to another land called Pakistan for shelter.

At the age of 13, she sat on a train that had promised to take her to a new land, a better one. The little girl sat on the floor of the train as she clutched her brothers and sisters while her uncle held a pistol in his hand, panting, his eyes searching and fearing the enemy—or were they even the enemy? The little girl couldn’t understand why the people of her land had wanted to kill her. So, she sat quietly waiting to see the better land. But before she could even reach it, the train reverberated with gunshots and loud screams. Her uncle shot the pistol and within this chaos, she opened her eyes only to find the small tin box of the measly train covered with splatters of horror. Out of a family of six, only three people came out of the train, holding hands as siblings do in a foreign land, leaving their beloved uncle behind in the medley of cries.

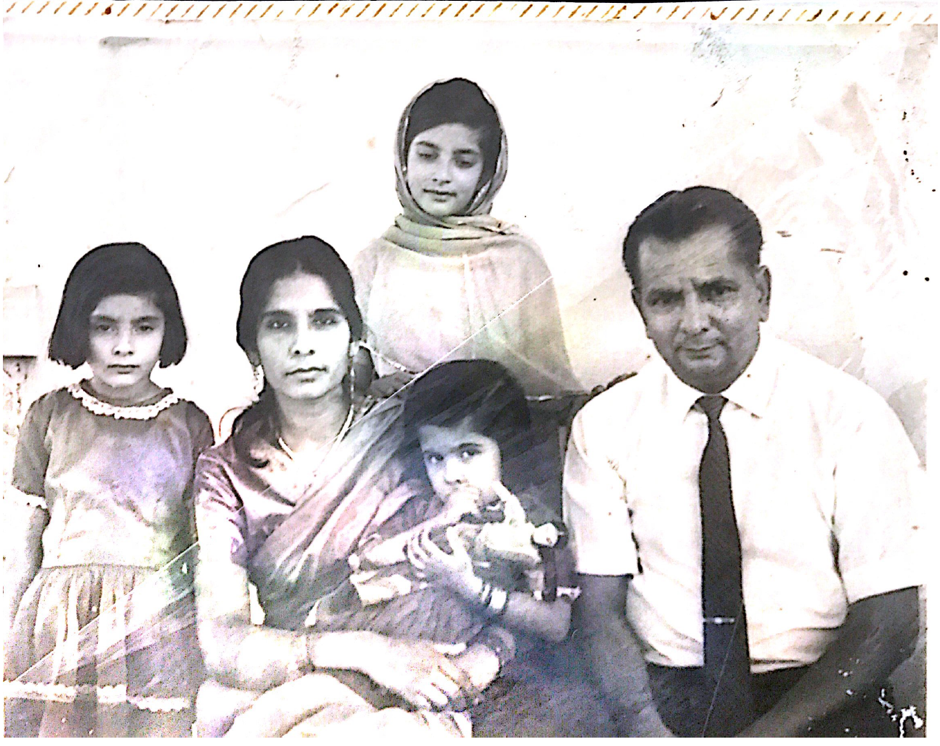

They grew up holding hands, crying, fighting and struggling. Until one day when, at the age of 16, Ammi let go of her siblings’ hands and went to another house, not as herself but as Zia’s wife. She was loved dearly by a man who did not have the money to support her or even shelter to offer. They shifted from street to street and then finally to a small house after he started working as a journalist. He wrote while she edited and together they created a strong passion for their small souls. Years passed, my grandmother was now a mother to four daughters whom she barely got to see. She worked at the government house in the morning, and at nights she would write about gunshots, blood, lost family, and her youth.

With time her skin withered and stretched while she raised her girls and traveled to distant places in order to serve the women of the land, giving them shelter, education, and a secure country. Ammi learned the spectrum of languages and religions, creating a community of people and expanding her family across Pakistan. All the while she worked on multiple projects with various NGOs, filing cases on the injustices against women, fighting against the exhausting patriarchy in the country.

Unfortunately, her world suddenly stopped when one day the members of her family decreased by one; Zia departed from his short life. Now Ammi stood alone in the house, not so small anymore. Her daughters would see their mother dissolve into lonesomeness. Ammi grieved the departure of her love, who had supported and loved her, bailed her out of trouble, and gave her a sacred space that enabled her to become an empowering force. Ammi was saddened because she knew life would not be the same, but she also knew that she could not stay broken. She still had to provide for her daughters andthe women of Pakistan. So, days after Zia’s death, Ammi mended the dents in her soul and drove to work like she normally would as if nothing had happened. She could not bring herself to share her grief with those who were grieving a greater loss.

She worked day and night sitting next to the broken hospital beds of the women who had been victims of acid attacks and women who were still picking up the pieces of their colonized youths and looking for shelter. She worked during the day and came home to her daughters who were going to college, learning to work in their late father’s press company, changing the car’s tires, fixing water pipes and paying the bills, all the while riding on the cluttering engines of broken motorbikes to get from place A to B. Soon Ammi’s family decreased yet again as her daughters took different last names and spread to different areas of Pakistan. She, on the other hand, retired to a one-bedroom house with a cat and her beloved lychee tree.

Now whenever I see her, I don’t just see my aging grandmother, I see her blossoming dimensions and the trail of the infinite selflessness of women. What value would I be to a family of such women if I still clung to Western feminist ideas that had sprung since colonization? What good is equal pay in a country where women are not even given the privilege to work? How can women gain education when they are murdered before even growing up? What good is Western feminism in a place where women are sold in the place of blood money?

A true woman and a feminist in Pakistan is not someone who fights for Western, materialistic notions of equality. Feminism in Pakistan is simply being there for other women. To be a feminist is to be selfless in helping other women be the best they can be in a country boiling with patriarchal ideas, a struggle that one can never seemingly win against the massive majority. But what we can do is stand united. We can be assets to women and to ourselves, as we find the raging force and power that rests within us and the women around us.

This is the lesson Ammi taught me. This is the legacy of our grandmothers.