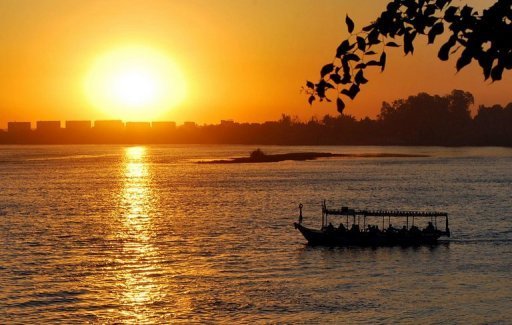

Amid the scenic landscapes of the Mardi Himal, a water crisis is quietly unfolding, intensifying with the growing specter of climate change. The ramifications extend beyond mere environmental concerns, casting a shadow over the tourism-dependent economy of this rural region in Nepal.

Mardi is just one location along the entire Himalayan belt of western Nepal, which has become increasingly vulnerable to the impacts of climate change due to shifts in temperatures and precipitation patterns. The socio-economic consequences are stark, with the Asian Development Bank projecting a potential loss of 2.2% of the country’s annual GDP by 2050 due to climate change.

In 2023 alone, the Mardi Himal trekking route, situated in the Annapurna mountain range, was impacted by this vulnerability as Nepal experienced below-average rainfall during the summer monsoon.

Kushal Yonjan, a teahouse operator who climbs 650 meters from High Camp to Mardi Viewpoint to fetch water for his shop daily, is one of many worried about the changing climate conditions.

“The shift in rainfall from summer to spring is arguably the most significant challenge we currently face,” he said.

Teahouse operators in Mardi collect rainwater during the summer for use in the autumn, when there has typically been an influx of tourists due to suitable trekking conditions.

However, the lack of rainfall during the autumn tourism season has resulted in water scarcity, making it difficult for tea shop proprietors.

Sarita Shahi, a teahouse owner, expressed her frustration, saying, “The trekkers are wasting thousands of rupees worth of water with each use, so even if I charge them Rs 100 for each use, what profit do I make?”

While efforts are underway up to Forest Camp in the Mardi route to address water scarcity, including the government’s construction of water reservoir tanks, locals say that water remains a costly resource for teahouses. Consequently, in Nepal’s trekking regions, some establishments charge fees of up to Rs 100 for trekkers to use their toilets, when in the past they were free. In contrast, others restrict restroom facilities exclusively for patrons.

Beyond the direct impact of climate change, the potential for a sustained decline in tourist arrivals due to unpredictable weather conditions along the route threatens to diminish tourism revenues.

The unusual spring rain, which has emerged in recent years, has discouraged trekkers from exploring the area during what has traditionally been a peak season for trekking in Mardi.

Santosh Gautam, a local guide, recalled how an unexpected spring downpour disrupted his holiday-season earnings during the Hindu religious festival of Dashain a year ago.

“We opted out of taking holidays to earn some extra cash,” Gautam remarked, “However, the rain deterred tourists, and all that we ended up getting was drenched.”

According to the Department of National Park and Wildlife Conservation, the number of visitors to the Annapurna region has declined by 50% during 2020, which Mardi is trying to urgently recover from.

Tourism contributed to roughly 6.7 percent of Nepal’s GDP and was a source of over one million direct and indirect jobs nationwide, as per a 2022 report by the World Bank. Significantly, about 80 percent of these jobs were found in remote and less developed regions, including Mardi. Gautam highlights that a downturn in tourism, worsened by erratic weather patterns and the slow disappearance of the region’s snow-capped mountains due to climate change, could have severe repercussions for Mardi.

Local teahouse proprietors often note that even fewer tourists hesitate to buy tea because of inflated prices caused by water scarcity. This has caused stagnation in the local tourism industry, prompting many owners to abandon their tourism-related ventures and seek better employment prospects abroad.

“I’m presently awaiting my European visa,” Shahi said. “Other villagers are also heading to countries like Qatar and Saudi Arabia in search of higher wages.”

Even with some locals leaving Mardi in hopes of finding employment abroad, Gautam envisions joining his fellow villagers as a lodge owner, eager to play a role in shaping the changing scenery of Mardi. However, he feels powerless as he observes Mardi slowly losing its beloved snow-covered vista to rising temperatures and its people to foreign lands as profits wane.

They are not satisfied with the thankless hard life here.”