TikTok Activating Youth Voices in Politics

Karan Menon, an undergraduate at the University of Southern California, uploaded a seemingly comedic video to TikTok on Feb. 7, 2021. In the 60-second-video, two characters – each representing the government and a farmer – argue over the introduction of a third character, the private sector, into the sale of agricultural products. During this playful skit, Menon outlines all the harms of an agricultural policy that the Indian government planned to introduce and how it sparked Indian farmers into protesting this year. Today, this video has almost two million views and about 400,000 likes. This TikTok is one of many others that keep users informed about major news and political updates.

A lip-sync to a trendy song to combat COVID-19 myths and a 20-second dance routine with catchy music on the rise of entrepreneurship in the Gen-Z: these are the kinds of TikToks that give today’s youth news updates, and they’re here to challenge traditional forms of news from broadcasts to long articles.

Ever since TikTok’s launch in 2016, it has become a dominant player in the social media scene. The app’s active users have grown 38 percent since 2019, the highest compared to other social media platforms. By enabling the creation of political videos that incorporate dance, humor and slick editing, TikTok is making politics more engaging for the youth. However, experts also worry that this may just be an illusion that is hiding the flaws of political discourse on such platforms.

“It’s a good way to be informed…in the form of entertainment,” said Beatrice Zemelyte, a sophomore at Northwestern University in Qatar. “If you don’t understand [a political] joke, you want to realize why you didn’t understand it and you read further.”

The entertaining audio and visuals of TikToks make political information and arguments more appealing, according to Orestis Papakyriakopoulos, a postdoctoral research associate at Princeton University’s Center for Information Technology Policy. “Politics becomes like a spectacle in that sense.”

There is a wide variety of features that users have to choose from to create compelling political narratives, such as skits, spoofs of news coverages, spins on interviews and mixing TikToks with sound, music and dialogues, according to Darsana Vijay, project assistant for platform labor at the University of Amsterdam.

Humor in particular is a dominant aspect of content on TikTok that hooks young people to political discussion. Something that adds to the amusing nature of TikTok is how content creators reject formal conventions of political comedy and videography with posts that have lo-fi production and evident effects like green screens. Humorous TikToks can also effectively communicate in a way that is non-antagonistic, according to Eddie Briseno, a 23-year-old who frequently creates political TikToks on his account with around 6,000 followers. “They communicate a lot, with very little,” he said. In one of Briseno’s TikTok’s, with more than 16,000 likes, he uses a comical filter that makes it seem like he has disappeared through a door while calling out the 2020 U.S. presidential debates for being solely composed of white men arguing over who hates Donald Trump more.

Oftentimes, posts go viral mainly because of their comedic presentation rather than a political resonation. Comments and post captions show that people frequently engage with or create videos just because they are funny, even if they do not have the same political ideology, stated Vijay. The pursuit of popularity and amusement raises questions regarding how meaningful political participation is on the platform. “To what extent can I say that this is political engagement when it’s so playful?” she said.

One thing that especially sets TikTok’s political discourse apart from other social media platforms is the prevalence of youth voices on the app.

“Having done comparative analyses, we’re really struck by just how front-and-center youth identities are on TikTok,” said Ioana Literat, an assistant professor of communication and media at Columbia University, in an interview with The New York Times. Unlike Twitter, where journalists and politicians are prominent, regular people are at the forefront of creating and engaging with political discourse on TikTok, stated Papakyriakopoulos.

As of February 2021, 60 percent of TikTok users are between the ages of 16 and 24, according to statistics by Wallaroo Media. Moreover, users are stimulated to use TikTok for long periods due to its design, studies show. The ‘for you’ home page becomes addictive through its stream of the latest videos that people can easily swipe up and down through. Unlike other platforms where the home page presents content only from those who you follow, TikTok generates a fresh set of posts from various users. Although it is not clear how the platform’s algorithm works, it tends to draw on videos from around the world based on the user’s interests, as well as videos that are viral.

TikTok’s political dialogue is also special in that a lot of it comes from young people’s personal identities and experiences, according to Literat. “Political dialogue on the platform is very personal, and youth will often state diverse social identities,” she said.

Hussain Zaidi, a 21-year-old Pakistani, makes TikToks on religious, sexual and gender minorities in Pakistan and the issues that they face. “It’s important to me as someone who’s from these different communities,” he said.

Although most of Zaidi’s content is posted to his Instagram account, where he has around 4,000 followers, he still records his videos on TikTok or replicates the format and trends of the app for messages of his own. TikTok-style videos are not only easier for him to create and tweak, their fun and carefree nature makes people remember the message associated with them as well, according to Zaidi.

Another demonstration of youth dominance in political discourse on TikTok is the formation of political hype houses in the United States. Hype houses are profiles where young TikTok influencers collaborate to create content, instead of using their personal profiles.

Twenty-three-year-old Matt Rein is the founder of the Democratic Hype House on TikTok where selected voluntary members create politically left-leaning content. Currently, the account has 16 members and about a quarter of a million followers.

“I think the appeal of TikTok and, specifically political TikTok, is that level of connection,” said Rein. “It’s refreshing for people, I think, to get their news from people who are the same age or the same background, etc.”

U.S. based political content also tends to appeal to youth across other countries because of their shared pop culture references growing up, according to Rein.

For some, TikTok is primarily a way to gauge trending opinions on the news, rather than to keep up with the news itself. Briseno, for instance, will take to Twitter at the start of the week to see the breaking stories in the news cycle. Related popular videos that then show up on his TikTok feed give him an idea of people’s reactions and interests.

News outlets, however, are taking note of the fact that young people are regularly on TikTok, according to Vijay. For some outlets such as the Washington Post, this calls for making accounts on the app, whereas for others it entails making their content more engaging for a youth audience even outside of TikTok. “They are trying to make the way in which they present news be more conversational, where they explicitly target the kind of repertoires and the kinds of formats that are appealing to young people,” she said.

However, experts warn political discourse on TikTok may also have its downsides for the youth. “I think the implications for younger people who are into politics and using TikTok are that they can very quickly fall into a bubble,” said Briseno.

This polarization could be associated with the design of TikTok, according to Vijay. Unlike Twitter, for example, where users traditionally engage in thread replies, TikTok’s comment feature is not as heavily utilized, she said. Commenting on the app would involve halting its flow which is more about watching and swiping next or creating a video response to it through the duet feature, she explained.

Although TikTok banned political advertisements in 2019, it has evaded responsibility for enforcing standards of healthy political participation, according to Vijay.

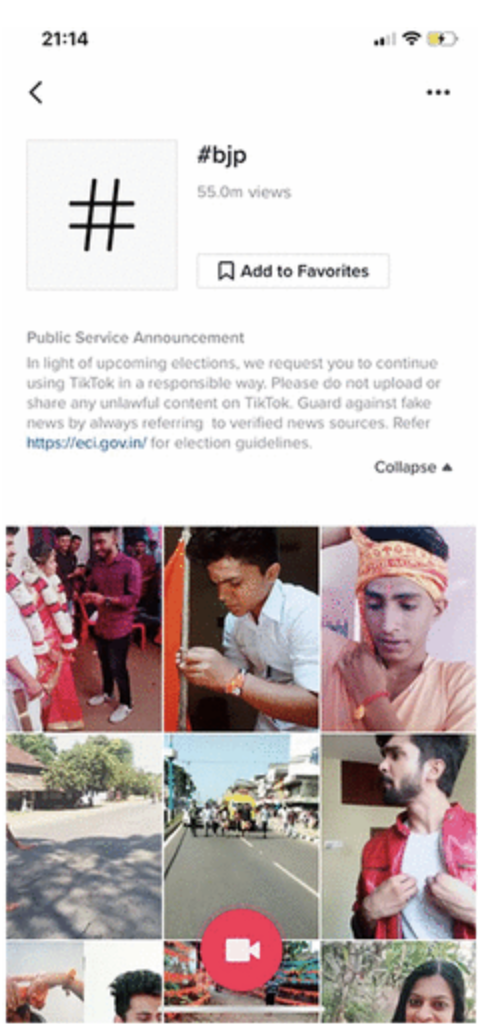

Even before the ban of political advertisements, efforts the platform made to curb harmful political content often had loopholes. This can be demonstrated by content that circulated the app in India after a 2018 Supreme Court ruling stated that women of all ages should be granted entry to Sabarimala temple in Kerala, a place that women of menstruating age have historically been prohibited from entering. The TikTok feed after searching #Sabarimala includes multiple thumbnails with saffron coloured items and clothing – a colour associated with the Hindu right wing Bharatiya Janata Party, BJP, according to a study carried out by Vijay. Many of the TikToks on the subject include spoofs of a television interview with Mary Sweety, a woman who tried to enter Sabarimala twice in 2018, to indicate that Mary is not a true devotee.

A year after the supreme court ruling on Sabarimala, the 2019 general elections were also held in India. During this time, the Indian election commission had prohibited parties from mentioning the topic in their campaigns. TikTok had also displayed a public service announcement to report any politically problematic content whenever someone searched for a party specific hashtag such as ‘BJP.’ However, issue-specific hashtags like #Sabarimala prompted no advisories on TikTok and everyday users were still able to disseminate content on the issue. The app saw a proliferation of right-wing content on the subject, which was not necessarily an accurate reflection of the discourse in Kerala, according to Vijay.

Moreover, TikTok has been found to align itself with the interests of governments, no matter how problematic the actions of those regimes may be. In 2019, an investigative report by The Guardian found that TikTok’s moderation guidelines for Turkey had banned content that was related to Kurdish separatism, as well as posts that defamed or spoofed the country’s founding father, Mustafa Kemal Atatürk, or its president, Recep Tayyip Erdoğan. Soon after, they also revealed that the app’s moderation guidelines before May 2019 prohibited pro-LGBTQ content, even in countries where homosexuality had never been illegal, according to The Guardian.

Moreover, as a Chinese app, TikTok has been accused of censoring content regarding political issues that threaten China, such as the Hong Kong protests and the oppression of the Uighur Muslim population, according to Vox. In the past, users have tried to mask controversial content in savvy ways. In 2019, for example, an American teenager used a makeup tutorial to spread awareness about Uighur Muslims in internment camps in Xinjiang, China.

Experts such as Literat are also concerned that political TikTok is not creating tangible benefits for young people. They still tend to fall prey to misinformation and are less likely to attend voting polls, said Literat.

Since shorter videos tend to do better on the app, it can also be difficult to communicate nuanced topics, said Briseno. Even 60-second videos get less engagement and the 15-second ones are the preferred length, according to Rein. “There are some really complicated topics we’ll talk about that I wish people could listen to for more than 15 seconds,” he said.

However, there are ways around this hurdle, as a TikToker could tell their viewers how to go and learn more about a topic elsewhere or they could find a way to make their statement in a shorter amount of time, stated Briseno.

“It is … a great constraint. And I think creativity thrives in constraints,” he said.