Media Majlis Hosts Panel on Viewership, Censorship, and Distribution

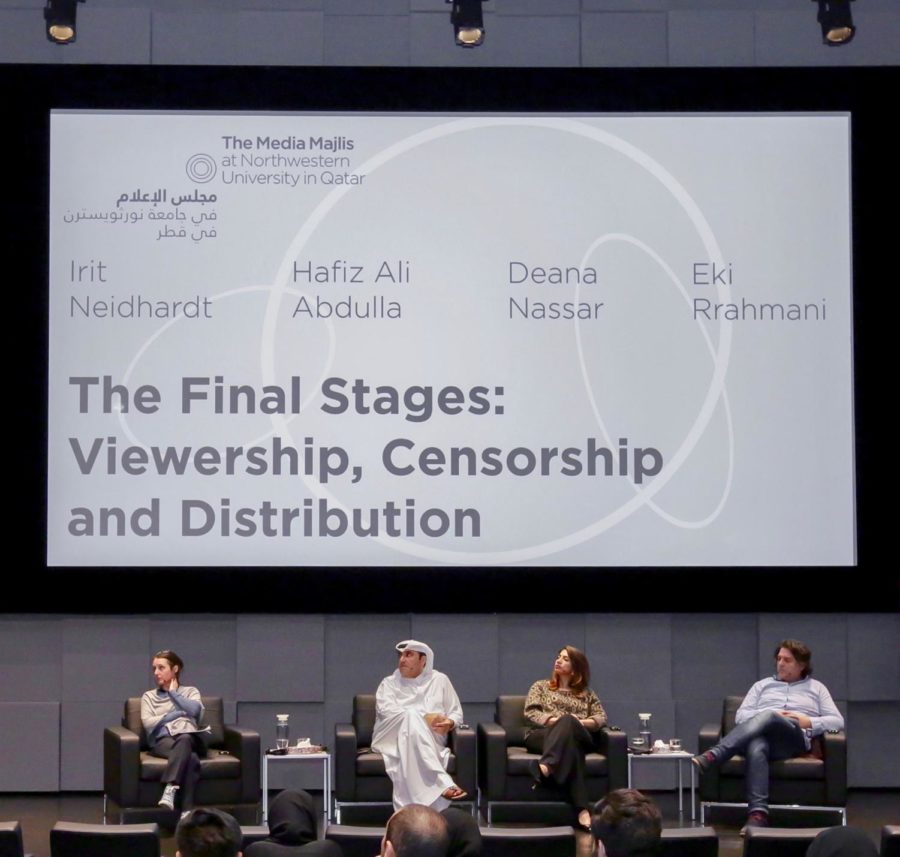

Irit Neidhardt, Hafiz Ali Abdulla, Deana Nassar, and Eki Rrahmani at the panel discussion. Photo credit: Media Majlis Facebook.

For the first time in history, two Arabs films were nominated for an Academy Award in 2018, which makes it more important than ever to discuss the impact of Arab film and the wide audiences it can reach, said Irit Neidhardt, founder of Mec film.

Neidhardt moderated a panel discussion titled “Final Stages: Viewership, Censorship, and Distribution,” at the Media Majlis at Northwestern University in Qatar on March 19. The panel consisted of Deana Nassar, the artistic director of the Arab Film Festival, Hafiz Ali Abdulla, a Qatari film producer and director, and Eki Rrahmani, a director at Al Jazeera.

Abdulla, who studied film in the U.S., said he considers movies to be a “visual language and a powerful medium that goes beyond what anything else could.” He said that the importance of Arab film resides in conveying ideas and stories on the Arab culture from different levels. He also added that institutions such as Doha Film Institute have helped Arab filmmakers in Qatar to overcome institutional, funding, and development challenges that they might face.

Nassar stressed the importance of exposure to Arab films in fighting the blunt stereotypical images about Arabs that dominate the media landscape. This is why, through the Arab Film Festival in San Francisco she directs, Nassar and her colleagues try to screen Arab movies in schools around the U.S. to increase exposure to more nuanced representation.

Nassar said that the Arab Film Festival “connects me to my own heritage when distance [from the Arab world] can make you feel disconnected.” She expressed the need for more Arab films and filmmakers in the cinema industry. However, she said she does not only support Arab films but also greater female representation and minority representation on the big screen in order to fight stereotypical thinking.

Panelists considered viewership not only from a U.S. perspective but also within the Arab world. “Qatari people love cinema a lot,” Abdulla responded when asked about the viewership of movies and tastes in the region. According to Abdulla, Doha is a viable market for movie distribution and viewership, because people in Qatar appreciate the artistic appeal of movies.

Rrahmani, who immigrated to the U.K. as a Kosovan refugee and whose passion for film started at a young age, used to throw stones at the police and then ask his mom if he made it to “telly.” Growing up, he was aware of the powerful role that the media plays in framing political messages and he has sought to convey his own perspective through the power of film.

However, Abdulla said Arab filmmakers should try to reach wider audiences rather than focusing on a niche local market. He expressed the need for Arab filmmakers to take advantage of global digital platforms such as Netflix and Amazon, who can provide a wider distribution to an audience that goes beyond the Arab region. “Filmmakers should think about digital distribution in platforms such as Netflix and Amazon, even before thinking about movie theatre distribution,” he said. According to Abdulla and Rrahmani, digital platforms people are leaning more towards watching movies on their smartphones and smart devices rather than in cinemas or on television sets.

“Smartphones are the new means of viewership,” said Abdulla. Rrahmani agreed and said: “Qatar has multiple opportunities that might not be available in other countries”.

According to Rrahmani, Doha is a small community that hosts distributors from all over the world who might be interested in helping filmmakers to distribute their films across different cinemas, film festivals, and digital platforms.

Drawing from his personal experience, Rrahmani had the opportunity to meet important distributors who are helping his documentary reach a wider audience digitally and across movie theatres. Constructing a solid network is more accessible here, he added.

The panel also discussed social and governmental censorship in the Arab world. According to Rrahmani, filmmakers should not give up telling stories because of censorship, but rather think of creative ways to get their stories out there while maintaining respect to the cultural differences.

According to Abdulla, censorship is a fluid concept that can go through a push and pull process, especially if it is social censorship. He gave the example of Capernaum, the Oscar-nominated DFI-funded Lebanese film, which was recently removed from the cinemas in Qatar and then brought back with some scenes omitted. Abdulla said that censorship can be navigated and should not stop filmmakers from telling the stories they want to tell.

Nassar had a different perspective. She argued that censored movies might be interpreted incorrectly, which might reinforce existing stereotypes about Arabs. She said that “it might be interpreted in a very reductionist way.”

Nonetheless, Nassar said that censorship can be complex and she still has conversations with her colleagues about it. One example that she struggles the most with is Palestinian films, especially the ones that have references to Israel, which might not be well interpreted by the Palestinian community itself. However, she concluded by saying, “we don’t want to put more censorship on people who are already censored.”

The panel also suggested that Arab stories need more coverage in Arab movies. According to Rrahmani, every story should be covered in its own way, but Nassar suggested particular stories that she wants to see more of. She expressed that Arab humor needs more coverage. “We are very funny and I don’t think it is appreciated as much as it should be,” she said.