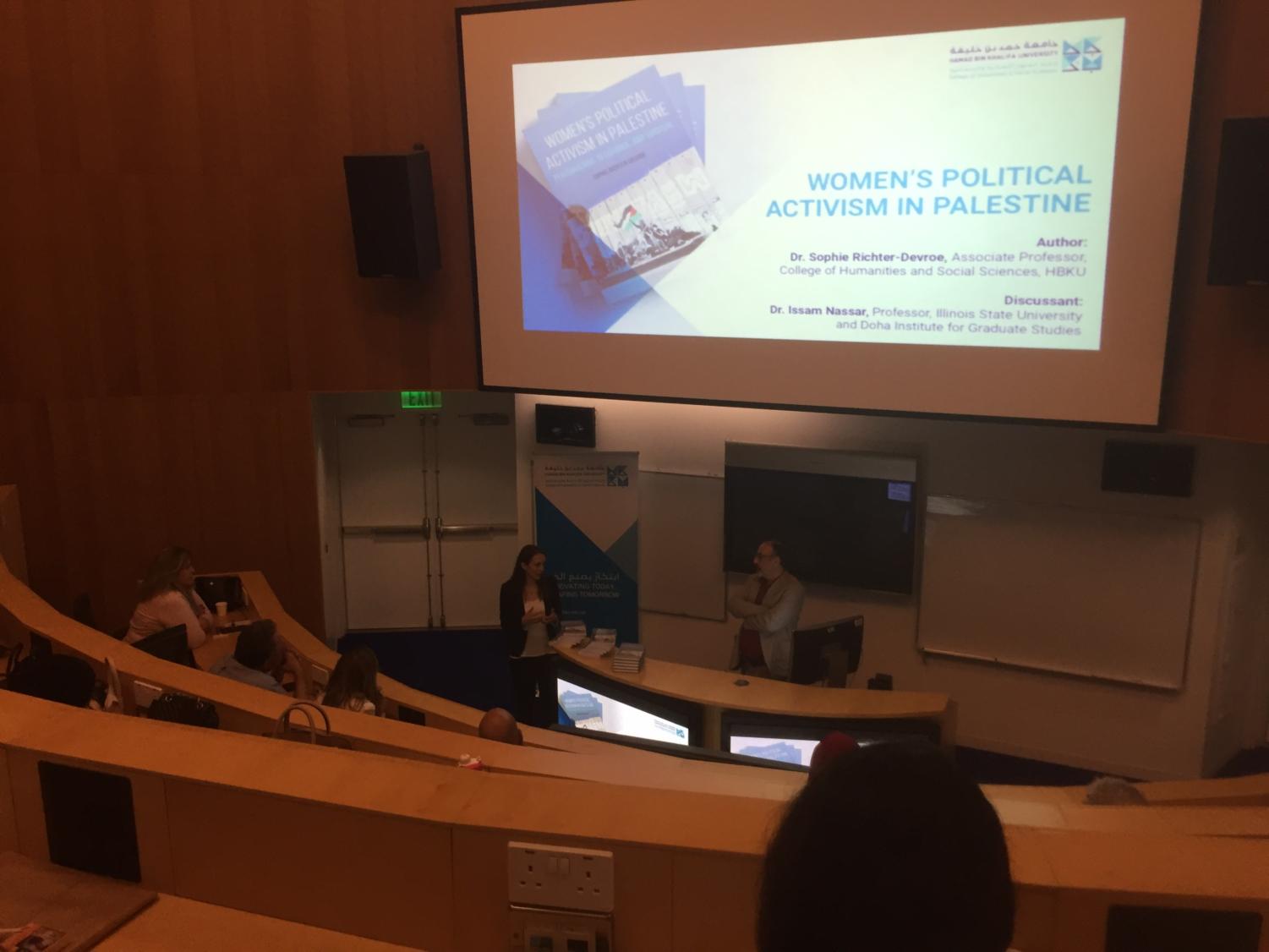

Women’s Political Activism in Palestine: Peace building, Resistance, and Survival

It took 12 months and 80 in-depth interviews for Sophie Richter-Devroe to discover that women’s political activism in Palestine is encompassed in their struggle to live a normal day-to-day life, despite the Israeli occupation.

According to Dr. Sophie Richter-Devroe’s, an associate professor at the Hamad Bin Khalifa University College of Humanities and Social Sciences, ‘sumud’ is a form of political activity for the stateless that needs to be understood and acknowledged in the context of Palestine.

In a talk at the college on April 9, Richter-Devroe shared her analysis of women’s political activism in Palestine. She was followed by Dr. Isaam Nassar, a professor at Illinois State University and the Doha Institute for Graduate Studies, who shared his commentary on Richter-Devroe’s work.

The classic liberal approach to female political activism, centered around feminist peacebuilding, does not apply in the case of Palestinian women, according to Richter-Devroe. She said that scholars should shift from this traditional perspective of looking at political activism as a ‘day to day’ approach, where political activism is integrated into routine and daily activities, in order to understand women’s political activism there.

According to Nassar, the female figure was always present in the history of Palestinian political activism. Palestine in the 1950s was portrayed and symbolized as a woman being raped and linked to women’s honor. This symbolism has always existed. It can be found in Palestinian artwork, such as Abdul Rahman Al Muzayen’s paintings.

Nassar said that Palestine was symbolized as a woman who gave birth to a nation of fighters. He argued that the representation of women’s activism was present from early on. However, it only gained attention in the 1960s with the emergence of women’s associations and the rise of women as civic activists and resistant fighters.

This institutionalization of the resistance movement frames women’s political activism within “macro-level thinking, [which] follows paradigms and lenses that led us to unions and parties and private and public, where everything is nicely distributed, but this way we are eclipsing the everyday politics,” said Richter-Devroe. She added that it is easy to get caught in seeking structured political institutions and claiming to understand political activity. When she was doing her fieldwork, Richter-Devroe discovered that women in Palestine do not attend the women-to-women groups, nor do they play a role in peacebuilding. Rather, they engage in the resistance through their day-to-day lives such as standing up to soldiers and trying to live a “normal happy life.”

Richter-Devroe said she saw women trying to live with dignity despite the disrupted political atmosphere. She argued that this should be in itself a form of political activism since they are trying to fight the realities of occupation and do not bend to it. This component is usually forgotten about in the liberal perspective, where political activism among women is reduced to organized political groups and institutions.

In the present, the mobilization to go and protest is very spontaneous among women in Palestine. Richter-Devroe said that they are ready to confront Israeli soldiers at any given time and they fight with stones.

According to Richter-Devroe, women often confronted Israeli soldiers first. Then the protests become institutionalized and labeled into “haraka silmiya,” which translates to peaceful movement, and “haraka unfiya,” which translates to violent movement. Due to the organized political institutions, men started claiming leadership of these protests and stood in the front lines, quickly becoming the symbol of the Palestinian resistance. However, Richter-Devroe argued that even if men took most of the credit, it was women who started these protests.

Nassar has a positive outlook on Palestinian authorities’ efforts to eliminate the discriminations among women as well as giving them more credit by trying to implement feminist policies. However, Richter-Devroe argued that these initiatives might not necessarily reach all women. She added that throughout her time in Palestine, women leaders of political parties were not happy about the institutionalization of resistance and with portraying men as the leaders of the resistance.

The audience engaged with Richter-Devroe after the talk in a discussion that was enriched by Palestinian attendees. “Dr. Sophie discussion was very eye-opening. Even for me as a Palestinian, as much as I research the topic, I have never thought about most [of] the perspectives that she introduces,” said Amina Awartani, a Palestinian who attended the talk. “I travel to Palestine annually and I have seen her observations, but the analysis that she provided was very fascinating.”