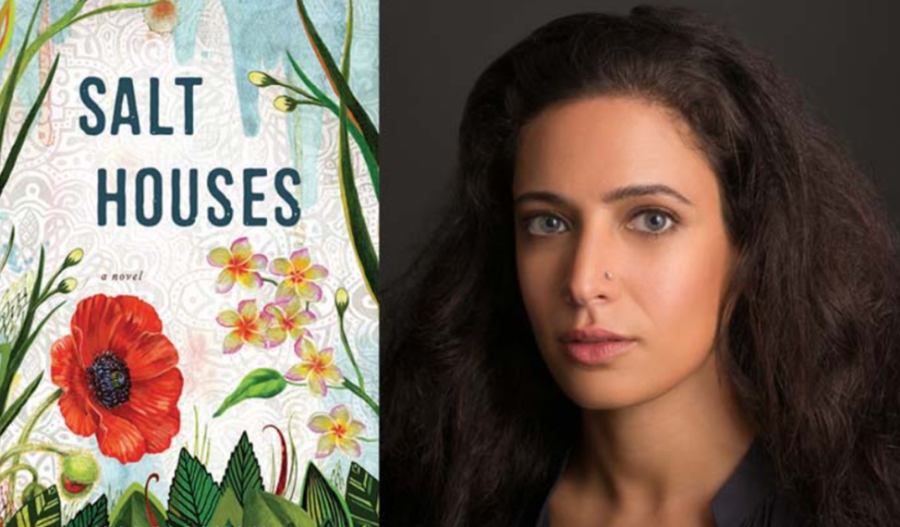

A Q&A with Hala Alyan

Not everyone has the luxury to maintain their culture, said Palestinian-American novelist Hala Alyan during a talk she gave at Northwestern University in Qatar on March 19.

During a series of events held last week at NU-Q, Alyan raised many important topics and sparked conversations about culture, home, and family. Alyan was invited to NU-Q to talk about her novel “Salt Houses,” which is this academic year’s One Book, One NU-Q program. The book is a multigenerational story of a Palestinian family that weaves together tradition and change, war and love, all told in Alyan’s lyrical writing.

After requesting to sit outside to take advantage of the Doha sun, a far cry from the current weather at her home in Brooklyn, Alyan had a conversation with The Daily Q about her writing, career, and identity. The interview has been condensed and edited.

You are here in NU-Q because of your novel “Salt Houses.” What is something you learned while writing it?

HA: I learned that I had more opinions than I thought I did about the vision of the book. I learned a lot about the process of publication. I remember when the novel came out just being so surprised by how many different moving parts there are particularly for bigger publishing houses, and how many people are involved, and how much goes into making a book that you walk into a bookstore and see. I learned a lot about fighting for my vision and I worked with a publishing house that was very lovely and for the most part did a wonderful job of taking what I had written and bettering it. But I also learned how to advocate for certain scenes that were really important for me to stay in [the book] and how to say no to certain things that I didn’t really resonate with. And then in the process of writing, I learned a lot about my family. I learned a lot about my relationship to Palestine, my relationship to identity. It is hard to write about diaspora for two-and-a-half years and not have to confront your own ideas about those things, so I think I just learned a lot about myself.

What was the transition between writing poetry and writing fiction like?

HA: To be honest, I always wrote both, I just hadn’t published in both. Throughout childhood and all through my teens I would write these little short stories, and then in my 20s I transitioned more into poetry. I think just because it’s easier, like it’s easier to write a poem than to write a novel. There’s an instant gratification that goes along with it so I think I was drawn to that. But the truth is I was always writing pretty much both around the same time and then the publication for the poetry came first. And the transition wasn’t so much in terms of me saying “now I’m going to write fiction,” as much as it was “now I’m going to write long fiction.” So that was a difficult transition just because it requires a totally different set of mental skills and creative muscle. The stamina is very different. If you write a novel, there is no instant gratification, you’re just working on that stuff for years. For the first [few] months you don’t know what it is, it’s just a jumble of ideas and names and you trust that it will develop into something. So, the transition was tough, I had to start being stricter and use more discipline. I would say that was the main takeaway from the transition: to use more discipline. I’ve never really needed discipline around poetry, I just kind of write when I want to, and when I feel inspired. If I wait to feel inspired to write fiction, I’ll never write fiction.

Your career path has led you to different areas such as from psychology to writing. How has your work in different fields changed you and the work that you do in those separate fields?

HA: I think they complement each other quite nicely actually, in that the currency for both clinical psychology and writing is storytelling. In [psychology] you’re working with other people’s stories and fractured narratives and you’re trying to make sense of it, and in writing you’re taking these ideas and you’re turning them into stories and you’re making sense of the chaos of an idea, a character name, a vision. I have to make a coherent whole out of disparate parts and I think that’s similar in both [psychology and writing]. I also think my training as a clinical psychologist helped me become more attentive, more mindful. It helps you ask better questions in therapy, and when you ask better questions in therapy you’re probably asking better questions as a writer. There’s a lot of human motivation and character motivation that is quite similar.

Growing up, you lived in many different places, so how were you able to adapt and still maintain your identity?

HA: I think I’ve struggled a lot on how to belong in the different places I’ve lived in and had access to. Beyond just being a member of a diaspora, [my family] also just moved a lot. So thinking of myself as Palestinian in Oklahoma is very different than thinking of myself as Palestinian in Beirut because it means different things; because the host country or host city has a different relationship to this identity. You learn to represent yourself differently, you learn to speak about it differently, you learn to adapt to it differently. And there is a little bit of an erasure that happens and a wearing down of the identity every time it has to be refashioned and repackaged to a different audience.

As a Palestinian-American, what is a challenge you face when trying to balance the two sides of your identity?

HA: You just learn to live in that borderland. It’s the struggle every hyphenated identity faces. We’re all just doing the best we can to hold onto the things that mean the most to us, and to be authentic to who we are. If that means that we love Nickelodeon and we pray five times a day then that’s our truth. I think that’s the best thing we can do for the future generation, to say “you can have all of it, you can have whatever combination of all of these countries and all of these cultures that makes sense to you.”