India and Pakistan: Religion-based casteism to define power structure

Correction (Oct. 30): This article has been amended to clarify the Pakistani government’s rhetoric on the Ahmadi population.

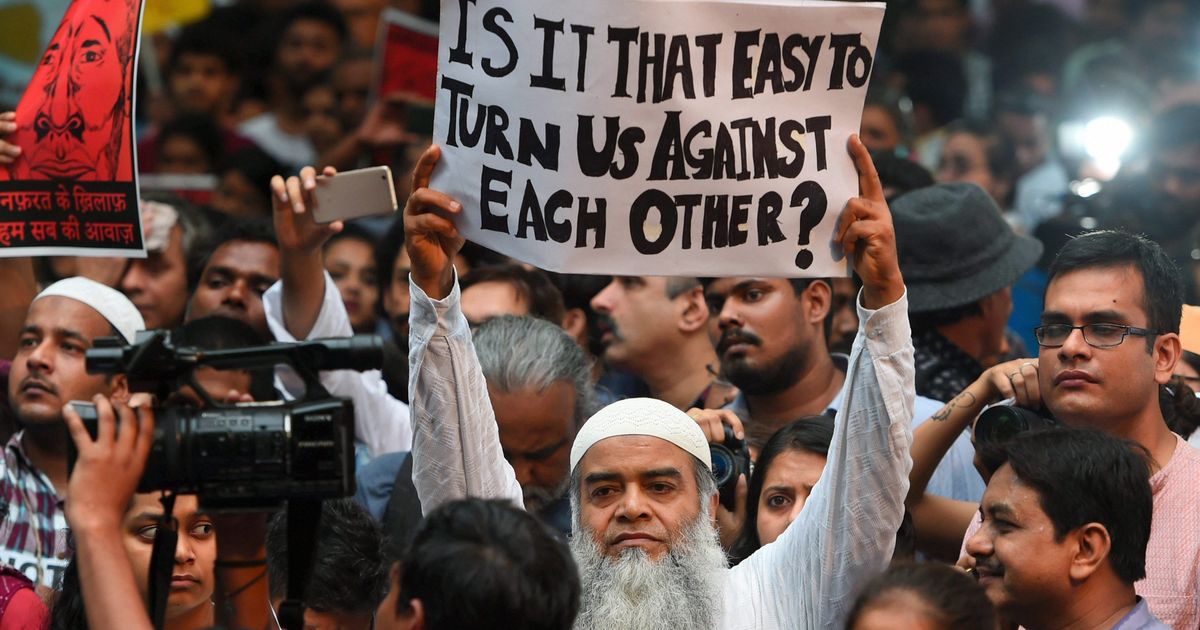

South Asia has seen a rise in religious fundamentalism, and India and Pakistan are two case studies that highlight how religion is used to marginalize certain communities, according to a virtual panel held on Monday.

The panel was organized by the South Asian Student Association at Northwestern University in Qatar and co-sponsored by NU-Q’s Liberal Arts program. Panelists discussed the rise of religious intolerance and sectarian violence in South Asia and focused on Pakistan and India in their examination of the roots of the problem.

The event was moderated by Khadija Ahmad, a representative of SASA-NU-Q, and featured speakers Toral Gajarawala, an associate professor at New York University Abu Dhabi and author of “Untouchable Fictions: Literary Realism and the Crisis of Caste,” and Usman Ahmad, a religious minorities rights activist in Pakistan.

Gajarawala focused on analyzing the intersectionality between religion, race, and caste in an Indian context.

She began by mentioning the case of Mohammed Akhlaq, who was murdered because villagers suspected he had slaughtered a cow, as an example of religious intolerance in India. She explained that the rise of hyper-nationalism in India is at the root of the problem and a powerful vehicle that induces hatred of minorities. “Hyper-nationalism and the demonization of minorities are two sides of the same coin,” she said.

She added that although nationalism can seem benign, its idealization of a certain type of citizen based on gender, faith, and caste is what induces segregation.

“India today is a particularly brutal example of the crisis of nationalism, and the specific form that it takes is Hindu nationalism, which imagines the ideal citizens as a Hindu caste male.”

Gajarawala added that this type of hyper-nationalism severely disadvantages minorities, in particular Dalits, who are deemed “untouchables.”

Gajarawala explained that the term Dalit refers to the lowest classes in India and that they typically include non-Hindus. Muslims in India are being targeted due in part to the fact that “the vast majority of Muslims in India are in fact lower class.” She argued that even though some aspects of segregation are so internalized that they go unnoticed, caste violence can sometimes culminate into very brutal atrocities.

Moreover, this has also led to the daily “boycotting” of the Muslim minority. “You can have, for example, the refusal by a doctor to treat Muslims in a hospital even during this COVID period. Or you might have something like a sign in a housing development that says no Muslims are welcome here,” she explained.

Gajarawala emphasized that although incidents that target minorities happen in a state that is indifferent and sometimes encouraging of such behaviors, it is important to understand that there has been “a transformation on behalf of the people” and that such new forms of hyper-nationalism have emerged and swept up people on an individual level as well.

She explained that this culture of targeting minorities “is happening in an atmosphere that legitimizes it but in which people are also acting as individuals.”

During the second part of this discussion, Ahmad spoke about religious intolerance and casteism in the Pakistani context.

Ahmad began by drawing a parallel between the caste system in India and the religious intolerance that exists in Pakistan. He explained that in Pakistan, religion is used as a dividing mechanism to keep people apart and define power structures.

“The present-day caste system comes…historically from the very complicated task of truly defining whether Pakistan is a homeland for Muslims,” he said.

He argued that this dilemma opened the way for other questions: “Who does this country belong to? Who will shape policies?” He added that “this attached Islam to the very heart of Pakistan’s identity. It essentially codified religion as part of the national DNA.”

Ahmad also explained that because national self-identity was so strongly tied to Islam, it created this notion of otherness. “Pakistan has codified this otherness through all its minority groups,” he said.

As an example, he explained that in order to be recognized as a Muslim in Pakistan, you have to negate the legitimacy of the minority Ahmadi community, who the Pakistani government claims are non-Muslim. “It is not sufficient for you to say that you are a Muslim. You first have to declare your Muslimness, but you also have to declare that Ahmadis are non-Muslims and heretics,” he explained.

Ahmad reiterated that the caste system in Pakistan plays out through religion and is used to marginalize certain communities. For instance, the 1984 anti-Ahmadiyya amendment that was introduced in Pakistan’s constitution under president Zia Ul Haq restricted the minority group’s religious liberty. As Ahmad highlighted, this law prohibits Ahmadis from calling themselves Muslim or “posing” as one even by simply smiling or wearing new clothes on religious holidays. An Ahmadi is punished by three years in prison if such behavior is adopted.

An audience member asked how caste violence could be understood in terms of intersectionality. As an example, they gave a hypothetical scenario of a woman living in the slums of Mumbai. This woman could be on the receiving end of violence, but because of her socioeconomic status, she could also perpetuate communal violence to express power and agency.

Gajarawala explained that with all the precarity and danger surrounding such an existence, “passing becomes a kind of option… it is a response to a kind of social crisis.” In other words, passing can be an act by which a person who belongs to a certain community attempts to assimilate within another one to enjoy some privileges.

Another audience member also asked about the role of social media in perpetuating certain stereotypes about marginalized communities.

Ahmad began by explaining that “when social media arose, there was this perception that … it was going to bring people together, perhaps make them more tolerant but that actually hasn’t been the case.” He argued that social media has rather “made people more entrenched in their views. We have seen this play out during the pandemic with a huge rise in hate rhetoric towards minority groups on the internet.”

Garajawala concluded that in order for minorities to reclaim their rights, there must be stronger laws and more inclusiveness. “There is a huge crisis for the minority at this moment in time. We have quite aggressive laws to prevent atrocities, yet so much brutality,” she said. “I don’t think it is just the result of the psyche’s resolve of people. The laws have to have enforceability and people have to have representation for that to happen.”